CIE A LEVEL ECONOMICS SAMPLE ESSAYS

7.4 Private costs & benefits, externalities and social costs & benefits

9708/42/F/M/23

The use of air travels leads to market failure caused by negative externalities.

With the help of a diagram, assess the extent to which a government can intervene to correct this market failure. [20]

Air travel is associated with market failure primarily due to negative externalities, which result in allocative inefficiency. This arises when the consumption or production of air travel imposes societal costs not borne by the individual user or producer. These spillover effects include increased carbon emissions, noise pollution, and environmental degradation. Allocative efficiency, which occurs when resources are distributed such that marginal social benefit equals marginal social cost (MSB = MSC), is compromised in this scenario.

In the absence of intervention, negative externalities occur when the consumption of a air travel produces a cost to society which is greater than that incurred by an

individual consumer/producer. This is also known as negative ‘spill-over’ effect.

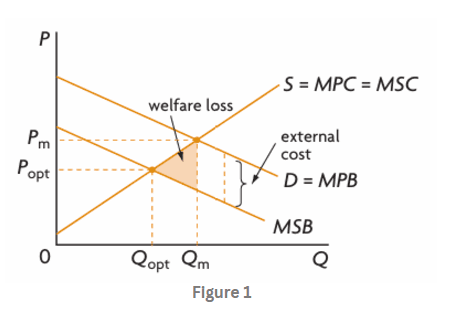

In Figure 1, the users of air travel have a demand curve, MPB, but when travelling, create external costs for non-travelers. These costs can be thought of as ‘negative benefits’, which therefore cause the MSB curve to lie below the MPB curve. This equilibrium neglects the external costs, leading to overconsumption of air travel. The vertical difference between MPB and MSB represents the external costs. The shaded area represents the welfare loss in the society.

To correct the market failure, governments can employ various measures, including taxation, negative advertising, and direct regulation.

Governments can impose a tax on air travel to internalize the externality. This increases the cost of flights, reducing demand and shifting the equilibrium closer to the allocatively efficient level. For instance, a carbon tax would raise the price of air travel, discouraging excessive flights and reducing emissions. The tax revenue can also fund renewable energy projects, further addressing environmental issues.

Another intervention is public campaigns highlighting the environmental impact of air travel. This strategy seeks to decrease demand by altering consumer behavior. As demand falls, the equilibrium quantity of flights moves closer to the efficient level, reducing the welfare loss associated with negative externalities.

Governments might implement regulations such as caps on flight numbers or emissions, or require airlines to adopt cleaner technologies. While this ensures a direct reduction in negative externalities, it may also lead to higher operational costs for airlines, which could indirectly increase ticket prices.

The effectiveness of government intervention is subject to several limitations. Taxation, while theoretically efficient, is challenging to calibrate. Accurately measuring the external costs of air travel to determine the optimal tax rate is difficult. Additionally, the effect of taxes on demand may take time to materialize, especially if air travel is considered a necessity or if consumers are inelastic to price changes.

Negative advertising, though less intrusive, is not always persuasive. The high costs of advertising campaigns may outweigh the benefits, and consumer behavior might not change significantly, particularly if alternatives to air travel are limited.

Regulation, while impactful, can impose substantial compliance costs on airlines, potentially leading to higher ticket prices and reduced accessibility for lower-income travelers. Moreover, such interventions might face resistance from the aviation industry, which is a significant contributor to global trade and tourism.

Overall, government intervention can reduce the inefficiencies caused by negative externalities. However, the net effect depends on the nature of the intervention and the specific circumstances of air travel. Taxation tends to be more effective when paired with complementary measures such as subsidies for green technologies or investments in high-speed rail alternatives.