The introduction of a trade union into a perfectly competitive labour market will always lead to higher wage levels and a higher level of unemployment.

With the help of a diagram, evaluate this statement. [20]

A perfectly competitive labor market is one in which many firms and workers interact, and no single employer or employee has the power to influence the wage rate. In such a market, the supply of labor is determined by the number of workers willing to offer their services at different wage levels, while the demand for labor is determined by the number of workers that firms are willing to hire at those wage levels.

In this context, wages are determined by the equilibrium point where the supply and demand for labor intersect. Firms are considered wage takers because they must pay the prevailing market wage to attract workers, and they cannot offer a higher wage without reducing their demand for labor. Similarly, workers are also price takers because they must accept the wage offered by firms in the market.

At this equilibrium point (as shown in diagram 1), the quantity of labor hours supplied (S) equals the quantity of labor hours demanded (D), and there is no involuntary unemployment. The market is efficient, with workers employed at the wage rate (W*) that balances supply and demand.

A trade union is an organization that represents workers in negotiations with employers, aiming to improve wages, working conditions, and benefits. The primary role of a trade union in a labor market is to increase the bargaining power of workers, ensuring that they receive better compensation and conditions than they would individually.

In a perfectly competitive labor market, where individual workers have little bargaining power, unions seek to raise wages by organizing collective bargaining efforts. By negotiating as a group, unions can push for higher wages than those set by the market equilibrium, creating a wage floor above the market-clearing wage. This is particularly common in industries where unions are strong and well-organized.

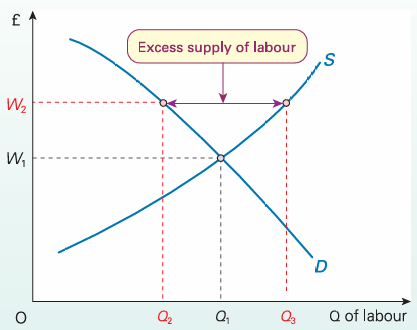

Diagram 2 shows intervention in the market by the trade union. The union wage (W2) is set above the equilibrium wage (W1). The introduction of a higher wage rate, set by the union, may increase the income of workers who remain employed. However, because the wage is now above the market equilibrium, firms may reduce their demand for labor, hiring fewer workers at the higher wage. As a result, some workers who were previously willing to work at the equilibrium wage may now be unemployed. This situation leads to an excess supply of labor at the union-negotiated wage rate, which is interpreted as increased unemployment.

Furthermore, firms may respond to higher wages by substituting labor with capital (machines, automation, etc.), particularly in capital-intensive industries where such substitution is feasible. This could further exacerbate unemployment as firms replace workers with technology. For example, if a manufacturing firm faces higher labor costs due to unionized wages, it might invest in automation to reduce its reliance on human labor, leading to further job losses.

While it is plausible that the introduction of trade unions into a perfectly competitive labor market will lead to higher wages and increased unemployment, this outcome is not guaranteed in all cases. Several factors influence the extent to which unions can raise wages and affect employment levels.

In industries where labor demand is inelastic, a wage increase due to union bargaining may not result in substantial job losses. For example, in the healthcare or education sectors, where personal interaction is critical, higher wages may not significantly reduce employment. However, in more flexible industries like manufacturing, where labor can easily be substituted with capital, unions’ wage demands may lead to higher unemployment.

If unions are successful in improving worker productivity through training or better working conditions, the negative effects on employment may be mitigated. In such cases, higher wages may be offset by increased output, allowing firms to maintain or even expand employment levels. This is because the increase in productivity increases the marginal revenue product (MRP), making it more profitable for firms to hire additional workers, even at the higher wage rate.

Moreover, the extent to which firms can substitute capital for labor depends on the industry and the available technology. In some sectors, the substitution of labor with capital may be relatively easy, leading to higher unemployment as firms automate tasks. However, in industries where human labor is crucial, such as personal services, automation may not be a viable option, and the impact on employment may be less severe.

While trade unions often succeed in raising wages, their impact on employment depends on various factors such as the elasticity of labor demand, the potential for capital substitution, and the ability of unions to improve productivity. Hence, the statement that the introduction of a trade union into a perfectly competitive labor market will always lead to higher wage levels and a higher level of unemployment is too simplistic, as it overlooks the complexities and context-dependent nature of labor markets.